Looking Positively Through Tough Times

COVID19 has done little to disrupt the worldview of most white-collar employees working from comfortable homes in the suburbs. If anything, quarantine has intensified our society’s addiction to fossil fuels and heightened the desire for near-immediate gratification of whims via next-day delivery.

As proof, the May Day Amazon and Target worker strikes received only fleeting media attention and did nothing to slow the daily parade of delivery vans though upper-class neighborhoods. When Texas lieutenant governor Dan Patrick suggested that grandparents sacrifice their lives for the economy, many Americans nodded their heads in agreement.

However, for those stuck in cramped city apartments or stranded in rural areas, the economy’s near breakdown has turned lives upside down. Low-wage workers in meat processing plants and the disproportionate number of people of color put in harm’s way have begun to question the premise of the economy for which they are asked to die. The media describes them with military imagery, using the term front-line workers to describe those serving fast food and providing nonessential goods.

In other words, the soldiers in the war against the coronavirus are blue-collar workers maintaining the unsustainable standard of living of the rich and middle-class. A surge in Google search terms related to DIY projects like baking bread and growing vegetables is evidence that many of these workers are sensing there must be another way to live. Burpee has reported an all-time sales record of seeds, and community gardens are popping up around the country as mutual aid groups share resources. What these people are experiencing is a subtle drift toward a different paradigm of goods and services known as a gift economy.

Gift Economy

The basic premise of the gift economy is that people receive goods and services as gifts instead of purchasing them with money. As Charles Eisenstein, author of “Sacred Economics,” puts it, money has no value in itself, but is rather an agreement that we could change at any moment. The negative side of our current agreement is a culture of greed and scarcity that traps some in a lifelong struggle to obtain the necessities of life, while others have more than they can use. COVID19 has only made the fragility of our economy more obvious by putting in the public eye its effects on the disenfranchised.

Gifts, in contrast, are given with an agreement of no payment. Instead, the receiver feels grateful and is inspired to give something in return. Unlike a money economy, this agreement fosters a cycle of reciprocity where each person ends up with what he or she needs. Anyone with a modicum of imagination can imagine the benefits of a gift economy: Everyone would have enough to eat, the earth would no longer be devalued as raw material for industry, students could study with no motivation but the love of learning, and individuals could pursue their life’s passions without economic reservations.

Gifts, Freebies, and Barters From COVID19

One barrier to the popular understanding of the gift economy is the modern connotation of the word gift. In a capitalist society, a gift is considered free because it doesn’t cost anything. However, as Native American plant biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer explains in “Braiding Sweetgrass,”. A gift in a gift society is not free because it creates a relationship.

Think of a box of free stuff at a yard sale. Taking an item from the box does not fill a person with gratitude. Or contribute in any way to creating a relationship between the giver and receiver. On the contrary, we take free items furtively and with some amount of embarrassment. If the neighbor instead were to personally give you the same item. Your relationship would change to one of reciprocity and mutual dependence. True gifts are given out of abundance and to satisfy the need of another, not because they lack value.

Giving also is not the same as bartering. When two people barter items, they agree that the values exchanged are equal. Bartering may substitute a physical item for money. But both currencies de-emphasize the relationship between the parties involved. Neither is inclined to feel particularly grateful after the exchange.

Because both leave with the same perceived value with which they came. Neither do they feel motivated to reciprocate, because both have already given?

When a person makes a purchase a bag of apples at Wal-Mart, they do not feel any obligation to the Walton family. Once paid for the person owns the apples and has a receipt to prove the rights to them. If instead, one barters a dozen eggs for the apples, the situation is no different. The person still owns the apples and do not feel indebted to the orchardist. Because our deal was an even trade. Receiving apples as a gift, on the other hand, creates a completely different dynamic that fills me with gratitude.

Gifts of Nature

To trace the origins of the gift economy. One needs to look no further than nature. Albeit red in tooth and claw, the natural world is also replete with unabashed gift giving.

Countless species have survived the eons-long battle of the fittest not by hoarding or counting costs. But by giving recklessly to those with whom they share symbiotic relationships. From birds cleaning zebra hides and crocodile teeth to leaf-cutter ants tending their fungus farms to honeyguides leading humans to beehives. The examples of commensalism are an embarrassment of riches.

For the above symbiotic pairings. The mutual benefits are immediately tangible: The crocodile walks away with clean teeth and the plover with a full belly. Other symbionts, however, gain rewards reaped only by future generations. For example, plants invest copious resources into packaging embryos into luscious fruits for other species to eat. And hopefully, deposit into the soil.

For still others, gifts given have no observable self-benefit whatsoever. In “The Hidden Life of Trees,” forester Peter Wohlleben describes a tree community that shares its own hard-won products of photosynthesis by funneling nutrients into a presumably long-dead stump. Thus keeping a fallen tree alive for decades through the sacrifice.

Reciprocity in Indigenous Societies

We tell children our economy’s origin story like this: Once upon a time, early people bartered their goods, trading commodities like animal skins for other goods such as grain or fish. If someone did not have a fish available for immediate trade. He or she instead would give something to stand in place of the value of the item, like a string of beads.

Eventually, our forefathers standardized these trinkets into coins. And — voila — our economy was born. Despite the many 6th grade social studies textbooks still propagating this myth, experts now concur that it is false.

Evidence indicates that bartering was an extremely rare practice in indigenous societies. Who instead operated under a gift economy. Anthropologist George Dalton denies the importance of bartering anywhere in the world, and Richard Seaford, in his book on early Greek society. Categorizes it as only a ritualized type of the gift-giving norm.

Detractors point to Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” as the definitive scenario of what happens in the absence of private ownership. They portray modern humans as alien colonists of Earth rather than as organic. Homegrown participants in its ecology.

These notions of property rights and feelings of separation are new phenomena. However, and the truth is that human societies have existed for thousands of years in clearly sustainable ways. From the time of the earliest hunter-gatherers.

Humans have received gifts of food, water, and shelter, and have reciprocated in turn. While it may be hard to imagine human activity benefitting nature. Kimmerer presents scientific evidence that indigenous methods of harvesting native grasses and trees strengthen plant communities. Martin Lee Mueller, in “Being Salmon, Being Human,” also describes how ceremonial salmon fishing in the Pacific Northwest. Allowed both human and fish populations to flourish.

The Path Forward during COVID19

Gift economies may not be the dominant paradigm worldwide. But they are still alive and well in some areas. A modern example of a successfully orchestrated temporary gift economy is the annual Rainbow Festival.

Where over 10,000 people peacefully and pennilessly inhabit a natural area for weeks at a time. Permanent gift economies have existed in Mali and in the Mount Hagen area of Papua New Guinea for thousands of years. Here, the only payment expectation is that a person will someday also give to another in need. Informal, small-scale gift economies exist in rural areas.

And among extended families and faith communities worldwide. Since the creation of the internet, the idea of a gift economy has gained momentum. Artists post their work free or on sliding scales of patronage. And open online courses like MOOCs allow free dissemination of knowledge. Blueprints for making everything from hand sanitizer to industrial tools are accessible.

Through websites like Open Source Ecology and Instructables. Mutual aid groups like the Buy Nothing Project, Share needs. And Food Not Bombs put gift economics into action at a local level by scheduling meetups in public parks where food and other items are given away. Rideshares, open-use bicycles and libraries-of-things are popping up in major cities. Even traditional public libraries now loan not just books but useful objects like cookware, bicycles, and even 3D printers.

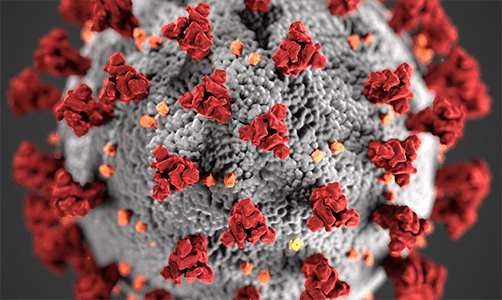

COVID19 is truly a plague that has caused worldwide hardship, suffering, and death. It is something we never would have chosen for our species to endure. We can decide either to wait for things to go back to normal or instead use this time of economic upheaval as an opportunity to rethink our economic system. COVID19 sudden appearance gives a sense of immediacy to what formerly might have been a purely theoretical pursuit. In gratitude for our lives and our humanity, we can recreate our relationships to each other and to the earth in a more sustainable way. Exploring gift economics is just the beginning of moving forward during covid19.